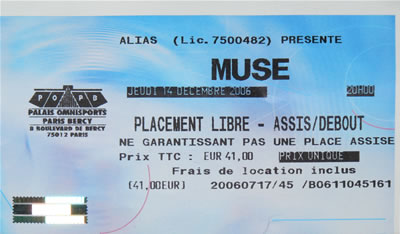

While attending the Muse concert in Paris Bercy on 2006-12-14, I took particular notice of something rather specific in the sound of the band: their ability to bring out a mix of major and minor chords with full distortion on the bass or guitar, sometimes even superimposed with crystal clear keyboards.

While attending the Muse concert in Paris Bercy on 2006-12-14, I took particular notice of something rather specific in the sound of the band: their ability to bring out a mix of major and minor chords with full distortion on the bass or guitar, sometimes even superimposed with crystal clear keyboards.

Now, if you've ever tried to play a minor chord with half the distortion Muse actually uses, you've certainly noticed how awful this can sound. I sure did, and hearing this sound great at the distortion and amplification levels of Muse was intriguing. What was going on ?

So I listened even more carefully to these songs I already knew. I had already noticed the live versions to be a bit different from the CD versions, but I tried to dissect these distorted minor harmonies to avoid their sounding awful, and all of a sudden .. Eureka!

Why minor chords sound awful with distortion

Wikipedia has a reasonably good explanation of what happens with minor chords and distortion, on the page about power chords. In short, the problem is the frequency relationship of fundamental to minor third present in minor chords (triads). After that, the obvious conclusion to reach, and the one most guitar players seem to be content with is "minor = no distortion ; full distortion = only power chords".

But there's a way out ! And Muse apparently found it, and it's not that hard : what sounds awful is the superposition of the fundamental and minor third (mediant) frequencies, just like what muddies major chords is the superposition of the major third and fifth (dominant), which is not in a low frequency ratio.

Let us compare frequency ratios and the overtones they imply:

- Power chord: C / G C = frequency ratios are 1, 1.5, 2, which sounds like 1, 3, 2, where 3 is the first overtone of the dominant, supposing its base frequency is removed: 2*1.5. Small numbers

- Major triad: C / E / G = frequencies are in a ratio of 1, 1.25, 1.5, which in the same way sounds like 1, 5, 3 under the same mechanisms. Note that equal temparement would make it 1, 1.26, 1.5, which doesn't sound half as well as a part of a chord.

- Minor triad: C / Eb / G = 1, 1.189, 1.5, which sounds like 1, 19, 3

- More mathematical details again on wikipedia

The high (19) frequency multiple from which the minor third derives means that the cross modulation resulting from the superposition of the fundamental and minor third will produce a slow fluctuation of level, with many unwanted harmonics muddying the spectrum, instead of the well-tuned growl one is looking for when adding distortion.

Harmony vs melody

An almost obvious solution would be to tune the minor third at 1.20X the fundamental frequency. This

removes the slow beating, most of the unwanted overtones. The only problem is that this does not sound

like an usual minor third, being too far from the usual frequency in equal temperament : indeed

1.2/1.189 = 1,01, which is only one-sixth of a semitone, making it sound out of tune in melody. And, of

course, the ratio works only for one specific tune. But the chords work: the player must just

avoid playing the notes outside a chord. First solution, and I did not notice Matthew Bellamy

using it.

An almost obvious solution would be to tune the minor third at 1.20X the fundamental frequency. This

removes the slow beating, most of the unwanted overtones. The only problem is that this does not sound

like an usual minor third, being too far from the usual frequency in equal temperament : indeed

1.2/1.189 = 1,01, which is only one-sixth of a semitone, making it sound out of tune in melody. And, of

course, the ratio works only for one specific tune. But the chords work: the player must just

avoid playing the notes outside a chord. First solution, and I did not notice Matthew Bellamy

using it.

On the other side of this harmony vs melody problem is the option of not playing the chord at all, and this is the one Muse seems to rely on mostly : when playing on a minor chord, at least as I heard in on this concert, they will typically play each note of the fundamental either alone or in a pair, but never as the full triad. This neatly solves the problem, even using equal of pythagorean temparement (which is common for guitars): Matt can bend the third oh-so-slightly up when it is played along with the fundamental, bringing it to 1.20 (a reasonably clean 6/5 to 1 ratio), or bend it slightly up too when playing it along with the dominant (a reasonably clean 3/2 to 6/5 = 5/4 to 1 ratio too), while playing the same mediant without bending on arpeggioes or melody parts, thus maintaining the frequency our ears are accustomed to hearing.

Although I didn't identify Chris Wolstenholme's frequencies, this being more difficult in the lower ranges used by a bass, I suspect he might be using this trick too, being a heavy user of distortion on his basses.

A bit of stretching

Finally, yet another option exists, and is the one I use most myself : stretched tuning. When tuning my Warwick in standard bass tuning, I always drop the E a bit lower than the frequency recommended by the tuner, and the G string a bit higher. This causes the low E to be a bit flat when played at low volume, but offers two advantages:

- at high playing volumes (and boy do I hit that E string !), where the high vibration amplitude causes a slight rise in frequency, the note will actually be more in tune, whereas it would sound a bit too sharp using a standard tuning.

- with the E being a bit low, the minor third interval from E to A strings, like F# to open A or B to D, which I often use, finds itself closer to the 1.20 interval than to the vibrating 1.189 in standard tuning, and sound less like a wolf.

I'd sure like to hear from fellow players on how they solve this problem on their own.

Photo Credit

The orange stomp box at the foot of my Warwick Corvette is a Colorsound Tonebender, an analog distortion pedal from the late 70s I used to play with my Les Paul Custom back when I hadn't yet discovered my instrument of choice. It gets along rather well with the bass, and I think it has been reedited by Colorsound, or can be found for cheap on eBay.